A new market analysis shows that state oil company Equinor is currently earning more money than any other Norwegian company ever has. Equinor’s huge profits, especially on its gas sales, are clearly linked to Russia’s war on Ukraine, but instead of being ashamed for profiting on a crisis, Equinor executives and many others at a major industry gathering last week claimed they’re proud to help provide Europe with the energy it now needs.

Among them is Kristin Kragseth, head of the state-owned firm Petoro, which is in charge of Norway’s own stakes in offshore oil and gas operations. She told newspaper Dagens Næringsliv (DN) that last autumn, “climate was the only thing we were talking about, climate, climate, climate.” She and other oil industry officials were on the defensive over how Norway’s oil and gas contribute to the climate crisis.

“Now we have more realism in the debate,” Kragseth told DN. With Russian oil and gas either cut off, unwanted or both, Norway’s oil and gas industry can help offset the shortfall and send as much supply to Europe as possible. Kragseth isn’t the only one relieved that the debate now isn’t only about how bad oil and gas can be for the climate and the environment, but also about how important it is to produce enough energy at prices that can return to more reasonable levels.

“The energy crisis and higher energy prices have been an eye opener for us all,” Øyvind Eriksen, chief executive of the large Aker energy group in Norway, told DN. Both he and Kragseth were taking part with thousands of others at last week’s large ONS conference in Norway’s oil capital of Stavanger, where he said he was feeling much more welcome.

Other energy industry officials and top politicians were also visibly relieved when they could once again meet and mingle at ONS, initially started up years ago as Offshore Northern Seas. Now the gathering is about much more than offshore oil and gas, with models of turbines for wind energy as common as those on display for oil platforms. Renewable energy is getting more attention, but gas was grabbing the most.

Many seemed vindicated as well when a non-Norwegian industrial tycoon like Elon Musk told reporters and a large audience at ONS that even an electric car builder like him thinks Norway needs to keep producing oil and gas. “I’m not one of those demonizing oil and gas,” Musk told his audience.

Musk called both fossil fuels “necessary,” adding that “we need more oil and gas, not less.” The Tesla founder thanked Norwegian officials, as he has on previous occasions, for providing lots of incentives for electric car ownership in Norway, but warned that fossil fuel will still be needed, at least in the short term “and especially in these times with Russian sanctions.” He also supports nuclear power plants: “If you have a well-designed nuclear power plant you shouldn’t shut it down, especially not now.”

Nuclear energy was once even more harshly criticized than oil and gas, but that’s changed dramatically since Putin invaded Ukraine. Now even liberal commentators were writing last week that activity in Norway’s North Sea can also be part of the climate solution, as opposed to the climate problem.

In addition to its oil, gas and wind resources, the floor of the North Sea can offer room for more carbon capture and storage (CCS) like that agreed between Norwegian fertilizer giant Yara and the Northern Lights CCS project owned by oil companies Equinor, Total and Shell. Carbon emissions generated by Yara at an ammonia plant in the Netherlands will be piped into the wells under the North Sea. More such projects are under consideration: German oil company Wintershall Dea is working with Equinor to see whether carbon emissions from German industry can be shipped for storage, possible through a pipeline to the North Sea’s botton.

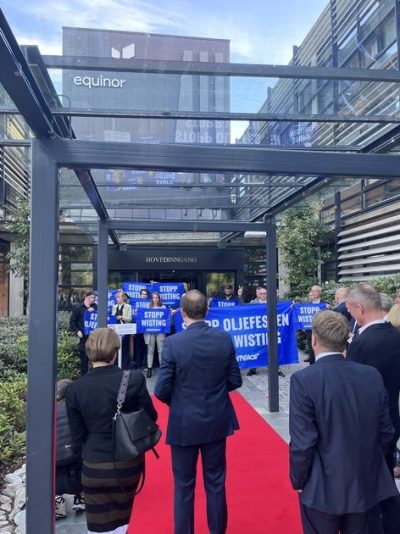

Climate and environmental activists remain worried, and continued to carry out some demonstrations of their opposition to the oil and gas industry at ONS. They were accused of setting off fire alarms during the gathering, blocked access to a garden party hosted by Equinor, and continue to demand a halt to all further oil and gas exploration, especially in sensitive Arctic areas.

That’s at odds with the Norwegian government’s policy to license new exploration areas in the Norwegian- and Barents Sea. The state oil directorate also released a report last week stressing how still-untapped gas resources in Norway’s offshore waters can play an important role in further energy supplies to Europe. The directorate encourages more exploration, further development of technology to get more out of fields already in operation and more development of offshore infrastructure. The potential is high, claimed the directorate, for exploiting more gas resources and boosting export capacity.

Anja Bakken Riise, leader of the environmental group Fremtiden i våre hender (The Future in Our Hands), Frode Pleym of Greenpeace and Frederic Hauge of Bellona are more than skeptical and concerned about the industry’s revived pride.

“We want to make it abundantly clear to Equinor and all of their influential guests that it is absolutely shameful to partake in oil-celebrating … while we find ourselves in the midst of a climate crisis,” Pleym said. He added that Greenpeace “won’t give up” until Equinor cancels plans for the Wisting field in the Barents Sea, as well as all other new oil plans, and concentrates on developing renewable energy.

Hauge generally agreed: “It’s fine that people are proud of their jobs, because then they’ll do a better job,” he told DN, but he questions the lack of debate over security on the job, not least after a devastating fire at Equinor’s gas processing plant at Melkøya in Hammerfest. He also worries that the industry hasn’t followed through on enough alternative energy projects, while stressing that current record-high profits won’t last. “The war means that they’re getting extremely well-paid … nor is there any debate over where the line goes on war profits.”

Riise is most concerned that renewed pride in the oil industry “will make it appear that we can just continue as before, and we absolutely cannot. I understand that we’re in a (war) crisis situation and that we must find some short-term solutions. I’m just afraid everyone will then just rest on their laurels.”

‘Constant struggle’

Riise was also distressed after a top Equinor official, Irene Rummelhoff, suggested during an ONS event that Russia’s war on Ukraine did not set off the current energy crisis. Rummelhoff called that a “misunderstanding,” blaming the energy crisis instead on “underinvestment” in all types of energy during the past several years, because of low prices and climate activists’ success in veering capital away from new oil and gas projects. DN reported that she claimed “campaigns” against fossil fuels “have scared some people, some funds, from investing in energy companies.”

Rummelhoff thinks it’s also “a constant struggle” for energy companies to obtain funding for new projects, even though the Norwegian government continues to provide controversial incentives for more oil and gas exploration, not least during the Corona crisis. She didn’t elaborate on why Equinor failed to pursue more alternative energy projects while she was in charge of them, nor why the company isn’t putting more of its current windfall profits into renewable energy projects. Norway’s own Sparebank1 Markets has estimated in a recent analysis that Equinor will be sitting on NOK 650 billion in cash by the end of the year, after earning around USD 70 billion during the third and fourth quarters alone.

Equinor has “lots of money but is a bit stingy,” Sparebank1 Markets’ analyst Teodor Sveen-Nilsen told state broadcaster NRK on Friday. He thinks Equinor has “too much money” and has been holding back on investments. “They could buy anything,” he added, or distribute large dividends to shareholders or buy back their own shares.

Equinor CEO Anders Opedal admitted that the company has an unusually large amount of money at present but won’t operate like a bank. “There’s no doubt that we are an industrial company and we will invest in good, profitable projects within renewable energy and oil and gas,” Opedal told state broadcaster NRK on Friday. He added that Equinor’s huge revenues “come with a lot of responsibility, and then it’s important that our owners including Norwegian taxpayers know we’ll manage the money in a good manner.” He noted that the company’s tax bill for the first half of this year alone amounts to NOK 230 billion, and will soon be paid.

Equinor is committed to boost its investment in renewable energy and Opedal claimed the company “is working actively to realize its ambitions,” both through its own projects and acquisitions in the market. The ambition includes having half of all investments in renewables and low-carbon projects by 2030.

Hauge of Bellona noted that “it’s positive to hear people talk about batteries, carbon capture and storage and offshore wind projects,” but time now for more action. His fellow climate activist Riise also complains that “there hasn’t been enough movement towards placing money in the necessary green solutions. It isn’t happening at a high enough tempo.” She blames politicians for failing to have a plan firm enough to “take us in the direction of meeting our climate goals in the Paris agreement.” There’s widespread concern that Norway won’t meet its goals.

Rummelhoff stressed that there are few alternative energy projects in which to invest and low profit potential, while demand continues to be highest for gas and oil. “There’s been an acknowledgment that we still need oil and gas,” Rummelhoff said, and that’s still where the profits are.

‘Oil price may collapse’

Not for long, according to another oil industry analyst. Jarand Rystad of Oslo-based Rystad Energy predicts another oil price collapse in 2024. “I think the oil price will stay at around the levels we see now (in the USD 90s a barrel), or go up and down between USD 100-130 a barrel this year and in 2023,” Rystad said at yet another ONS event.

“But in 2024 comes a collapse,” he added, because the oil industry is now mobilizing lots of new capacity. He noted that it can take from six months to two years to drill a new oil well, and if more drilling continues now, there will be much more supply in 2024. That can drive the price down, maybe to as low as USD 20 a barrel depending on “dynamics in the market.”

He thinks the gas market, meanwhile, will remain tight and prices high because Europe needs to function without Russian gas. Rystad believes either the Russians will halt supplies or Europe will, “if we manage to say ‘no thank you.'” Italy and Germany will play the biggest role in what happens.

Norwegian media was quick to pick up on the sudden shamelessness of the oil industry, as it ships more gas to Europe and profits in return. “Yes, it’s a new reality now, and a lot has happened in the world this past year,” editorialized newspaper Dagsavisen during the weekend. “Concern for the climate has fallen on the political agenda because acute crises emerged over the energy situation in Europe, but the industry’s ‘comeback’ during a brutal war is more than inappropriate. It’s uncomfortable.” The paper noted that the industry itself is responsible for its earlier “underinvestment,” and that should not be allowed to derail Norway’s so-called “green restructuring.”

NewsinEnglish.no/Nina Berglund